{Biswas-Diener & Dean, 2007. Positive Psychology Coaching: Putting the Science of Happiness to Work for Your Clients.}

How much of our happiness, talents, accomplishments, aspirations, values, hopes, and beliefs about life’s meaning are under individual control? Much of what seems personal to us has a clear genetic component. Knowing where our biological blueprint affects us and where it does not strongly influences our ability to facilitate change.

If genetic factors are half of the influence on personality, the other half is life circumstances and personal choice. Life circumstances are largely outside our control, yet today’s choices will shape tomorrow’s circumstances, maybe in small or large ways. Similarly, genetics is not static, but choices shape our makeup. Even something that seems utterly out of your circle of influence, your age, for example, is not so; just wait for a day, and you will be a day older, and waiting for a day is totally under your control.

Coaches and other change agents focus on personal and behavioral areas under individual control, making personal choice the primary tool for change. The personal choices most relevant to happiness relate to goals, social relationships, and cognitive habits. Choosing just the right pursuits, connecting with worthwhile people, and developing upbeat, positive thinking strategies can maximize your ability to live the life you want. You can manifest your happiness by making smart choices. You have power over desires, interactions, and thoughts. You can probably identify many successes in setting goals, tending to relationships, and attending to your thoughts. It might be just a matter of shaping your awareness to bring your past successes to bear on your current choices for the better.

Goals

A vision for future outcomes can fill your daydreams, keep you aware during tough times, and help you persevere when there are troubles. Goals are natural motivators in life, and there is a direct link between goal pursuit and happiness.

Goals help organize our lives to meet crucial existential, social, personal, and psychological needs. They provide a direction to coaching work and a baseline for evaluating the effectiveness of our services. Coaching has largely been built around goal setting. Goals give us direction, motivate us, and structure our time, actions, and decisions. Working toward goals gives us a sense of meaning, and achieving goals provides a sense of accomplishment.

To better understand our progress toward goals, we make them specific, measurable, and timelined. We set small, attainable, and realistic goals to optimize our chances for a favorable outcome. The SMART criteria provide the foundation for goal setting. But they do not point to whether this is the best route to client growth.

Establishing the parameters of “attainable” and “realistic” goals is tricky. Our job is to encourage personal transcendence, helping our clients surpass self-imposed limitations. Setting too low “attainable” goals risks holding our clients back from their potentials. On the other hand, too high a goal risks our client’s failure and the associated self-worth and ability issues.

What, then, are “good” goals? How can we tell which are worth pursuing?

One suggestion is to take stock of an individual’s resources. Resources most relevant to an individual’s goals are the best predictors of her satisfaction.

Coaches and clients can measure if goals are realistic by evaluating client resources and determining whether these are relevant to the goal at hand.

While the SMART system is based on goal content, positive psychology research introduces additional features to focus on when setting goals.

Goal Orientation

How individuals think and talk about their goals impacts their happiness. Whether people strive for positive, “approach” goals or outcomes or avoid negative outcomes by “avoidance” influences happiness, satisfaction, subjective health, and distress and anxiety levels.

A coach listens for approach- and avoidance-related language and asks clients questions that encourage them to reframe negative, avoidant goals as positive ones.

But, again, a balanced view is advised since some degree of avoidance from harm should always be considered; the environment is not entirely benevolent all the time, and the best intentions might have some strings attached with a price tag.

Keep an ear open for goal orientation and content when working with clients. Crafting goals as approach goals will increase their chances of finding happiness.

Avoidant goals can detract from happiness. A few well-placed questions can lead to important insights and possible reframing strategies.

Goal Content

Certain goals, such as those related to intimacy, spirituality, and generativity, lead to happiness. In contrast, others, such as power-related goals, do not.

The coach is impartial to client decisions about goal content, cautioning the client non-judgmentally about potential hazards and drawbacks as they also look at the positive aspects of the relative merits of power-themed goals.

The coach should clarify the guiding principles when research findings point one way, but the client wants to go another. For example, asking permission to share such research non-judgmentally might be one principle to follow when, for example, the client has power-themed goals that are likely to cause long-term relationship problems, ultimately leading to dissatisfaction.

Goal Motivation

Ultimate success is not only a matter of what we want but why we want it, influencing how we feel about the goal and the outcome.

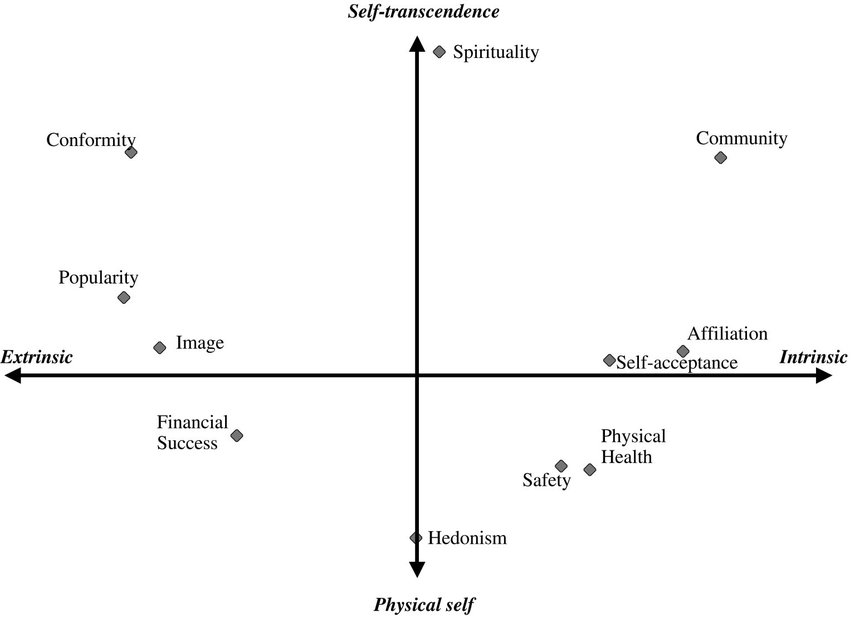

Intrinsic goals are inherently satisfying, such as working at a job because it is challenging, enjoyable, and makes a viable contribution to society. On the other hand, extrinsic goals serve some external reward, such as working in a job only because it pays well. Intrinsically motivated goals are positively associated with subjective wellbeing. These goals are more highly valued, more personally rewarding, or provide feelings of growth and autonomy. On the other hand, extrinsic motivators such as popularity, physical attractiveness, and money are frequently accompanied by anxiety and interpersonal problems. Extrinsic motives often are associated with competition and control that contribute to stress. (Sheldon & Kasser)

{Self & Other; Inner & Outer

Fame is the other; connection is the self

Wealth is the other; fulfillment is the self

Status is the other; competence and achievement are the self

Power is the other; autonomy is the self

Good looks are the other; self-worth is the self}

Inherently satisfying goals have a larger happiness payoff than those serving other needs.

Extrinsic goals are often resources to achieve desired outcomes. One might achieve the same outcomes through intrinsically motivated goals.

The coach and client can look for a “goal chain” and carry it to its conclusion to see such a sequence.

By valuing money, good looks, and other extrinsically motivated goals, people replace the things they “really want” with these more shallow goals. What does the client want at the most fundamental level? What would good looks be in service of, or what might money be spent on? Articulating these more positive goals can be a breakthrough for personal success and lasting fulfillment.

People across all cultures strive toward the same outcomes (health, more money, strong family units, etc.) and mentally and psychologically organize their goals similarly. The two major dimensions people think about their goal content and motivation represent the physical self, the self-transcendence dimension, and the intrinsic, extrinsic dimension.

{Grouzet et al., 2005. The Structure of Goal Contents Across 15 Cultures}

Goal Conflict

Goals are tied to values, and because people hold many values dear, an individual’s goals sometimes are at odds with one another. When goals collide or conflict without easy resolution, somatic complaints might arise; aches, stress, sleeplessness, and even illness. Moreover, goal conflict or ambivalence results in goals less likely to be acted on but more likely to be thought about, becoming psychologically toxic because people end up dwelling on the problem and forgetting to act on a solution.

Rumination and anxious thinking further deepen the “rut,” creating a feeling of being “stuck.”

Coaches can help deal with ambivalence and other forms of goal conflict by exploring client values underlying goals, encouraging clients to draw cost-benefit charts, or using written assessments to generate forward momentum.

When too much thinking is the problem, one can get caught in the common trap of believing one can think their way out of goal conflict. In contrast, the solution might be to stop all thinking and just act.

Helping a client shift focus from thinking about how to solve the problem to acting on the problem feels empowering and kick-starts forward momentum.

In addition, the client can take a holiday from his conflict for a day or two and commit to some small action when he returns from his “stress holiday,” such as interviewing someone who has faced a similar dilemma or writing a paragraph on what the goal would look like in a perfect world.

Goal Anxiety

It is natural, and even helpful, to experience mild anxiety around one’s most dearly held goals.

Investing heavily in goals can promote good feelings as well as create anxiety. Progress toward or attaining a goal leads to positive emotions and protects against worry. Alternatively, “failure impact predictions,” believing that failing to achieve the goal will be emotionally upsetting, produces anxiety.

The general advice for healthy goals (Ken Sheldon) is to strive for enjoyable goals, develop both short- and long-term goals, seek out goals you value, consider changing your goals if they’re not working, and don’t focus overly much on ego-gratification goals such as popularity or material objects.

Evaluate your goals concerning their relevance to your resources, their approach-avoidance orientation, and the degree to which they are extrinsically or intrinsically motivated. Consider your past investment in a particular goal, and examine setbacks in working toward that goal. How did you react to the setback? Did you take time off from the road? Throw additional resources at the goal? Revise the goal? Think about how to apply these insights from your life to your coaching sessions.

Consider a structured format for working with goals. For example, will you use the idea of matching goals and resources based on their relevance? How might you discuss the idea that goals might be intrinsically or extrinsically motivated? What additional questions about goal orientation (approach/avoidance) might you add to your goal-focused interviews?

Goal-striving can arouse anxiety.

How much of your client’s anxiety might be a natural by-product of investing heavily in a meaningful outcome, and how much might be a symptom of rumination? How might you assess and address your client’s anxiety across various stages of goal development and achievement? How does anxiety affect your client? How much can she tolerate before feeling burdened or stuck?

Social Relationships

Good relationships are vital for emotional wellbeing. Humans belong to groups, interact with others, and start families. Physical touch, affection, and interpersonal interaction are necessary for flourishing. In contrast, solitary confinement, banishment, and shunning are extreme social sanctions against wrongdoing. Close, trusting relationships are the single unifying factor differentiating the happiest from the least happy people, outpacing intelligence, income, or educational status where happiness is concerned. Lack of attachment is linked to ill effects on health, adjustment, and wellbeing. Feelings of belonging provide psychological safety to take risks and attend to work and other concerns.

Beyond a certain point, additional friends may not matter concerning their psychological benefit. Friendships, as all interpersonal connections, require ongoing maintenance, like occasional positive interactions. The more friends and acquaintances a person has, the more time and energy will be spread thin. Perhaps most of us do not need to seek out any more friends than we already have.

Social concerns are a large part of everyone’s life. However, people may overlook many of the most rewarding relationships available to them: helping relationships. Helping others feels good and promotes our sense of worth and competence. Whether people volunteer time, donate money to a worthy cause or mentor a student, helping translates frequently to large happiness gains. For a work-personal life balance, it can be helpful to carve out “protected time” with children and other family members.

High-quality relationships at work facilitate handling conflict, being resilient, open, feeling positive, alive, or excited, and feelings of mutuality, and can foster personal growth, creativity, and inspiration. These personal connections keep us enthusiastic about current projects and motivate us to develop new ones.

High-quality connections are not a matter of chance. One can meet and connect with coworkers, identify good social fit, and tend to relationships to benefit both parties whenever possible. One might see such connections as opportunities to benefit from a new viewpoint, learn new things, access new skills and talents, and generate new ideas, motivating one to invest their energies in this worthwhile cause.

How might you work with your clients around social connections? Consider taking stock of client social resources. They could list people they are closest to on the job and off. What do these people offer concerning fun, support, like-mindedness, challenge, or opportunity? How could you use role-play for relationship introductions, problems, and maintenance?

Thinking Style

Psychological outlook comes from learned mental habits employed in interpreting life events. For example, happy people tend to take responsibility for their successes. They relish their achievements. “I deserved this promotion,” they say after hearing the good news. More pessimistic individuals, on the other hand, tend to avoid taking personal responsibility for achievements, shifting the responsibility to random chance.

Most people make unconscious attributions about the cause of successes and failures. However, thinking biases can be controlled, and all impact emotional wellbeing.

Perfectionism:

Coaching clients are generally motivated, hard-working, excited by progress, and eager to explore new ideas. They are mostly driven individuals interested in self-growth. High achievement is linked to high standards, which can be counterproductive when inflexible. Failure is inevitable, and competition creates second places. Second place among one hundred might have outperformed 98, but perfectionists would see it as “not first place.” It is a biased mentality discarding success for a narrow definition of perfection, which is simply an internal standard for evaluation.

Remind your client about the distinction between perfection and excellence, and explore some other possible gauges for success.

First, consider past performance to encourage clients to compete against themselves rather than those with whom they must maintain positive relationships. Consider articulating a definition of “excellence” in a given instance to have a clear success criterion.

Finally, consider exploring the gap between your client’s aspirations and chances of success; the smaller the gap, the happier your client will likely be.

Distress tolerance:

Folks are surprisingly capable of bouncing back from difficult events. But many people consistently underestimate their ability to cope with life’s setbacks. Mostly imagined fears hold people back from taking risks, making changes, or picking up where they have failed in the past.

The hidden self-talk might amount to, “I won’t be able to stand the sense of loss, frustration, sadness, embarrassment, or failure.” {Albert Ellis would say, “What will happen to you? Will you die? Will you be sad for the rest of your life without hope for recovery? How could it be possible that you cannot withstand some negative feeling?”}

Potential losses loom larger in the mind’s eye than potential gains. Loss aversion impacts people’s decisions dramatically. People have a habit of focusing on the immediate, worst emotional reactions to failure or hardship.

Ask the client to create a timeline to examine a negative consequence (failure) over the long term. Certainly, they have experienced failure in their lives and flourished afterward. Ask about unpleasant emotions two months, six months, and one year down the road.

Your clients can tolerate more hardship, pain, and frustration than they are aware of. Mine their experience for doing just that. It is likely that many setbacks or problems they have faced, they now remember as important learning moments, pivot points, or wisdom sources.

Black-and-white thinking:

This thinking habit overlooks the middle ground. Western logic categorizes things into distinct groups and thinks in either/or patterns. Ideas of a partial win, a moderate success, or a simultaneously promising and discouraging goal seem contrary to Western culture. Dichotomies simplify information and leave it in a clear, easy-to-understand and use format. The problem arises in holding rigidly on to simplifications when they have no merit. Learning to loosen up can lift an enormous weight from our shoulders.

Chronically happy thinking:

Positive thinking can be an acquired habit. It is a conscious effort to seek out the positive, even as one acknowledges the inevitable negatives. “Wellbeing in this sense is living with your eyes open” (Carol Ryff).

Part of happy thinking concerns where attention is focused. We can savor personal wins, compliments and encouragements, and strokes of good fortune only if we are aware of them. People vigilant for praise, success, and inspiration tend to find it. Folks who savor accomplishments feel good about their past while hoping for the best in the future. Taking time to look for and appreciate the shiny side of life is a powerful tool to stay inspired, energetic, and motivated. An upbeat outlook predicts future success. Optimism is a major personal asset. Increasing hope is a powerful tool to move clients forward. People in a good mood are more likely to look favorably to the future, just as hopeful folks are more likely to be in a good mood.

How might you work with your clients around positive thinking? Will they permit you to challenge them when you hear perfectionism or black-and-white thinking? Consider exploring with your clients how their current thinking is helping or hindering them. How might you use the research showing that revising thinking is a relatively easy habit to master and is beneficial?

Conclusion

Happiness is mildly pleasant and common but not permanent. It includes some (but not complete) satisfaction with most (but not all) life aspects. Most of us are naturally mildly happy and adapt to this state even in the face of new life circumstances. Finally, happiness is not caused by a single thing. Instead, it is influenced by various variables, from personal values to individual genetics. Most importantly, happiness is largely a matter of good choices under personal control. Understanding personality aspects that are difficult to change supports working with clients on more productive areas concerning happiness, including developing healthy goals, maintaining good relationships, and engaging in positive thinking habits.