{Boyatzis, 2008. Leadership development from a complexity perspective. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 2008, Vol. 60, No. 4}

Multilevel sustained change

Leader development involves a leader learning the behavioral habits of effective leaders and, with effort and intent, changing their ways to the desired becoming.

A coach assists in designing and executing change efforts, resulting in wanted, compared to unwanted consequences and sustainable changes. The process follows the emergent discoveries of intentional change.

Individuals live in nested hierarchies, forming relations with others as dyads or couples, including boss or subordinate relationships; interrelationships within a team, group, or family; the move expands into organization, community, country or culture, and global levels of organizing. Organizing points to a complex, dynamic, fluid, and sometimes ephemeral relating of self and others with information and energy flow channeled in designed or emergent ways.

Sustainable change at any one level must involve developmental work at the levels below and above it. Effective team development requires effort at the individual level, among various dyads, and at the organization and community levels. It takes effective leadership on many levels to effect sustainable change. The link between the individual and the team change is the team leader. In the same way, the link between the team and the organization change is the organization’s leader.

Energy and information flow are the primary means for effective leadership to ensure sustained, desired change. Within-level purpose and among-level interaction produce adaptive behavior. The first degree of interaction is effective leadership, and the second degree of interaction is through the formation and use of social identity groups.

Among-level interaction involves interaction between individual, dyad, small-group, and organization. Interaction with larger levels requires social identity groups, often in the form of coalitions and effective leadership.

Change dynamics

Leadership effectiveness entails behavior, thoughts, feelings, and perceptions, which comprise a complex system and combine into actions, habits, or competencies. Sustained, desired change requires intentional effort and is likely experienced as an epiphany or discovery.

For the self-aware person, change occurs as a set of smooth transitions. To a less self-aware person, the changes will seem surprising. The same goes for sensitivity. A heavy demand load on leaders may reduce their ability to sense subtle alterations in themselves and others.

Tipping or trigger points are transition events at which emergence, or discovery, occurs. At times, a small behavior shift produces a dramatic change in effective leadership behavior, such as repeated verbal encouragement of collaboration in an organization with no effect on performance, turning into a transition event when one act of collaboration invokes a change in others’ behavior.

Emergent events start a new dynamic through the pull of specific attractors.

The concepts from complexity theory are discontinuity, tipping points, self-organizing patterns of equilibrium or disequilibrium and emergent events, and the multi-levelness and the interaction among these levels through leadership and reference groups.

Theories of change may hide or ignore emergent dynamics, and the actual change process remains the black box. How the change is engaged, and proceeds are left unclear as the inputs and outputs are explained in detail in these theories.

Desire as the Driver

Adults develop characteristics of effective leaders only if they want to be leaders. Extrinsic motivation to satisfy other people’s desires, to get a certificate of completion, or to move up to advance a career may produce compliance or approval but not necessarily change. Commitment is linked to the person’s will, values, and motivation. Intentional change requires investing the energy and time to acquire emotional, social, or cognitive competencies.

The impact of leadership development training is relatively short-lived, and the new behavior exhausts or atrophies within months, despite the immediate impact of the training.

Five Discoveries of ICT

Leadership development involves the iterative emergence of nonlinear and often discontinuous experiences. Moments of emergence are named discoveries in ICT:

Discovery #1 Ideal Self: Who do I want to be?

Discovery #2 Real Self: Who am I?

Strengths: where my Ideal Self and Real Self are similar.

Gaps: where my Ideal Self and Real Self are different.

Discovery #3 Learning Agenda: building on my strengths while reducing gaps.

Discovery #4 Experimenting with being a leader. Practicing being a leader.

Discovery #5 Resonant Relationships that help, support, and encourage each step in the process.

First Emergence: Seeing His/Her Desired Future

With the emergence of a new awareness, the discovery of who the person wants to be, rises into consciousness as a vision of a core identity with strengths, an image of the desired future, and a sense of hope that it is attainable.

It is important to take time to articulate the formulation of the ideal self. Positive visioning creates new neural circuits and arouses hope, stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) and increasing openness, cognitive power, and flexibility.

In addition to focusing on established strengths, capturing the energy inherent in new possibilities and the emotional driver of hope is essential. To repeat, it is wise to insist that the person has a well-articulated ideal self and personal vision. Each client or student should write his or her vision for the future and talk about it with trusted others.

Exercises for visioning, tests to reveal aspirations, and talking with close friends or mentors help envision the desired future. These explorations should take place in psychologically safe surroundings.

Second Emergence: How Does the Person Act With Others?

The greatest challenge to an accurate self-image is for the person to see himself or herself as others do.

Before a person can change, he or she must know what he or she wants to maintain. Acknowledging discrepancies between the real and ideal self can be a powerful change motivator. However, the distinction between the person’s ideal and ought self is an important additional discovery.

Using multiple sources for feedback for insight and psychological tests to determine explicit aspects of the real self, such as values, philosophy, traits, and motives, help the discovery.

Third Emergence: Developing a Learning Agenda

A learning agenda focuses on development. It is a plan for things the person wants to try and explore, articulating a way to get to the desired self, using strengths, and building on some weaknesses.

A learning orientation arouses a positive belief in one’s capability and the hope of improvement, resulting in people setting personal standards of performance rather than normative standards that merely mimic what others have done.

A performance orientation can evoke anxiety about whether we really can change.

Strange Attractors

Attractors are Lorenz attractors that pull people toward them, individually or in groups. The positive emotional attractor (PEA) and the negative emotional attractor (NEA) determine the context of the self-organizing leadership development process.

Dissonance occurs in social organizations unless there is an intentional investment. Over time, deterioration occurs. Social interaction is essential for the human emotional system to function. Life and career cycles are also dramatic in their destabilizing effect. A person occasionally seeks novelty and change.

Intentional change theory fosters a disequilibrium. The person is likely to seek readjustment as a new self-organized system. The PEA becomes destabilizing as it pulls the person toward her ideal self. By focusing on possibilities, a person’s PSNS is aroused. In this PSNS state, the person is calm, and her immune system functions at its relative best; the body is renewed. Learning is enhanced, and changes initiated during this stage are more successful.

The NEA is also involved. It arouses the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and helps humans deal with threats. In a threatening environment, the NEA pulls a person toward defensive protection. Among other bodily adjustments to the threat, cortisol is produced, which inhibits neurogenesis and overexcites older neurons, rendering them useless.

Sustaining change is challenging and must be driven by a powerful force. Articulation and awareness of the Ideal Self activate the energy of the PEA.

To try a new behavior, a person often needs permission to let go of old habits and try new ones. This permission typically comes from interacting with trusted others. Clients or students must spend sufficient time in the PEA to prepare for their time in the NEA and adaptation stress. In this way, the coach is a cheerleader (predominantly positive), guide (conscious of the person’s state and progress), and provocateur (pushing, pulling, and cajoling the client or student into the PEA and NEA when appropriate).

Fourth Emergence: Experimenting With New Habits

Experimenting and practicing effective leaders’ behavior characteristics, eventually, the person gains the emergent awareness of his ability to use the new behavior well and then sees himself using it in real settings. For this emergence to occur, the coach should help the person find safe settings to practice effective leader characteristics.

Fifth Emergence: Others Helping Us

Supporting relationships provide a sense of identity and create a context within which people interpret progress on desired change, the utility of new learning, and even contribute significant input to the formulation of the Ideal Self.

Helping relationships work on the trust a person experiences and the safety from that trust. Coaches, and friends, can be mediators, moderators, interpreters, and sources of feedback, support, and permission for change and learning. Working on goals in multiple life spheres (e.g., work, family, recreational groups) enhances the targeted improvement of leadership competencies.

Helping relationships become a new reference group that encourages change and increases the confidence to change, providing observations, feedback, and support, wherein the person develops a sensitivity to cues that signal a possible relapse.

The ideal self as the driver of intentional change

{Boyatzis & Akrivou, 2006. The ideal self as the driver of intentional change. Journal of Management Development Vol. 25 No. 7}

Change requires sufficient drive and intrinsic motivation. A person’s aspiration influence her activation. A person’s vision and visualization of desired behavior become elements in her performance output in many domains of engagement.

The ideal self is the driver of intentional change in one’s behavior, emotions, perceptions, and attitudes, as described in intentional change theory (ICT).

The ideal self: Image of the desired future, Hope, and Core Identity

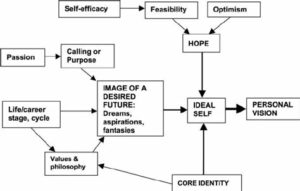

The three major components converging into the articulation of the person’s ideal self and the resulting personal vision are the core identity, hope as the affective driver, and the image of the desired future.

The ideal self contains imagery of the desired future as the articulation or realization of the person’s dreams, aspirations, and fantasies. This image is cognitive, yet it can be fueled by the affect resulting from one’s passion, dreams, and values. The person’s dreams of the desired future state are a function of her sense of calling or purpose in life; driven by her passion, values, operating philosophy; and stage in life or career.

The ideal self is emotionally fueled by hope. Optimism and efficacy are seen as the main determinants and generators of hope and, therefore, key determinants of the ideal self. Hope is caused by the degree of the person’s optimism, and it is the expression of her degree of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy determines the person’s perceptions of possibilities. Hope is an experienced state and, thus, an emotional state. This differs from conceptions of hope as mainly cognitive, such as Snyder’s hope theory. The cognitive processes that assess and judge the feasibility of that which is hoped are less critical or reflective judgmental and more affective.

Core identity is the relatively stable set of enduring individual characteristics, like unconscious motives and traits, as well as roles adopted consistently in social settings. The core identity is the personal context which provides the historical and continuing aspects feeding the ideal self and the autobiographical themes that make the vision coherent and intense.

The ought self

In contrast to the ideal self, the ought self is someone else’s version of what they think your ideal self should be. Social pressures for role conformity may bend you to be a good group member. To the extent this becomes intentionally integrated into a person’s ideal self, there appears to be no conflict among the various selves. But if they are somewhat different and a person works toward the ought self, at some point in the future, she will awake and feel betrayed, frustrated, and even angry at the time and energy wasted in pursuit of dreams and expectations that she was never passionate about.

The motivational core

The ideal self is the evolving, motivational core and the locus of positive emotion within the self that drives the personal vision, which, in turn, drives sustainable, intentional change.

At other levels of human and social organization, the collective, shared desired images of the future, shared hope, and shared sense of a group’s identity and distinctiveness become the shared vision that drives sustainable, intentional change at these levels of organization.

The degree of activation of a person’s ideal self is related to increased consciousness, salience, and coherence; increased mindfulness about the ideal self and its components, the salience or importance of the components, and the coherence of the image are the three paths leading to a healthy and robust (i.e., meaningful and useful) ideal self.

Mindfulness answers the question, “Is the ideal self articulated, and explicit?”

Salience or intensity of desire for the components of the ideal self relates to “Is the ideal self important?”

Coherence or a holistic inclusion of the person’s desired life and future answers, “Is it integrated with the rest?”

Ideal self leads to a personal vision

Discovery, or conscious realization of one’s ideal self, may emerge as a new insight or awareness in a discontinuous break with prior consciousness about one’s aspirations or future. The ideal self provokes a phase change in the person’s change or adaptation process and invokes intentional change.

Discoveries are facilitated by the observations, interpretation, feedback, and encouragement of others the person trusts. A personal balance sheet promotes developing a person’s learning agenda and then a more articulated learning plan, experimentation, and practice with new behavior, feelings, and perceptions, and the eventual desired changes in either the person’s actual behavior (their real self) or her aspirations and dreams of her future (ideal self).

In all these discoveries, articulating the ideal self serves as a strong personal vision, engaging the positive emotional attractor, enabling an assessment of a person’s capability as it may help or hinder movement toward the ideal self.

Positive affect

Positive affect is a state of high energy, full concentration, and pleasurable engagement. In contrast, negative affect is a general dimension of subjective distress and unpleasant engagement that subsumes a variety of aversive mood states, including anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, fear, and nervousness.

Trait-based positive emotion becomes the driver and the substance of the ideal self. Once the force of the ideal self is activated, it generates self-regulation and organizes the will to change and direct it toward self-actualization. The ideal self activates the person’s will and, by association, the possibility of increased self-monitoring, especially concerning progress toward or behavior consistent with the purpose reflected in the activation of the person’s will and the decisions and choices, such as the decisions to sacrifice certain immediate rewards for the sake of accomplishing more important and often long-term goals.

Arousal of the ideal self engages the positive emotional attractor and its impact on intentional change. Arousal of fear or avoidance motives engages the negative emotional attractor and impacts the person defending herself or being forced to contemplate adaptation not previously considered. Defensive emotions result in a likely shift in perceptions of the environment as more threatening or merely anticipating that future events will be more threatening, giving rise to defensive or hostile actions and withdrawing or inhibiting new thoughts and alternative ways to approach a situation.

Hope: the affective driver

Hope assumes an openness to the future and imagination and feeds creativity.

Snyder’s conceptualization defines hope as a positive motivational state based on a sense of goal-directed agency energy, pathways planning to meet goals, and goals.

Goals provide targets for thought processes. They may be verbal descriptions or visual images. They vary in terms of temporal frame and degree of specificity. They may reflect positive or approach goals or negative goal outcomes.

Pathways thinking involves the perception that a path to the hoped future is feasible, similar to the notion that self-efficacy affects the person’s experience of hope by creating a belief in the feasibility or possibility that the desired future or state might occur.

Self-efficacy mediates knowledge and actions. A person’s perception of capability determines what goals are chosen, how much effort is invested, and how long one persists in facing obstacles or aversive experiences. This component of hope feeds into core identity through the person’s awareness of her enduring capability and dispositions.

Optimism is also a component that affects the person’s experience of hope. People who are more optimistic and experience positive emotions set the feasibility, or possibility, marker high. Meanwhile, more pessimistic people set this marker low.

Control-related constructs are classified as beliefs about agent-ends relations (personal control beliefs), beliefs about agent-means relations (efficacy expectations), and means-ends relations (response efficacy, optimism). Pathways thinking is parallel to means-ends thinking.

Agency thinking is the motivational component of Snyder’s definition of hope and seems close to a combination of the first two sets of beliefs (agent-ends and agent-means).

The positive emotion involved in the experience of Hope is central to the power of the ideal self. Positive emotion emerges from the sense of agency or self-efficacy and the belief that there are feasible routes to accomplishing the hoped-for image or state. All of this adds to the degree of the person’s optimism, resulting in the aggregate positive affect encoding the images or dreams of the future and the person’s core identity.

People who are relatively lower in self-efficacy and optimism experience less hope. Hope should be attended to for continued energy and commitment to the effort of change.

The image of the desired future

The dream or image of the desired future is the content of the ideal self, the picture of what is hoped to be. It may or may not imply a person has to change. Even if the person feels to be in a perfect state and the dream of a future state is a continuation of the current state, to maintain or sustain this present condition, all dynamics of ICT apply here as well, and it is necessary to activate the ideal self for the investment of time and energy needed.

Dreams and fantasies express one’s inner needs, wishes, and fears. The dream or image may come from one’s values and philosophy. Personal history, enduring dispositions, character strengths, and positively valued qualities seen as strengths become continuous input to one’s values and are interpreted by one’s operating philosophy.

The career and life stage is a prime mover of the desired future images, as is a person’s discovery of their purpose or calling.

Dreaming about the future, experiencing hope, and arousing images of the desired future lead to arousal of the PSNS and all of the positive effects on new learning. The power of the ideal self is emotional and physical and involves neuro-endocrine processes of renewal and healing.

This is in contrast to the stress response, which results from contemplating what one fears or wants to avoid or evaluating or judging the worthiness of one’s dreams.

The core identity: one’s context and resources

Our concept of core identity consists of social identity in group memberships, affiliations, connections to different social collectives, and personal identity involving one’s attitudes, traits, feelings, and behavior.

A strength-based interview of ten to 20 people with whom one works, lives, and plays, asking them to recall “a time when I was at my best,” can fuel one’s self-confidence and boost the sense of self-efficacy and, therefore, hope about the future. Each respondent is asked to tell about the person’s actions and their impact on others. All these stories will point to themes and patterns about how the person acts when they are “at their best” and constitute an inventory of their strengths as observed, experienced, and remembered by others.

Coupled with a clear image of the desired future and the accompanying sense of hope, the positive effect of the core identity yields a potent ideal self and driver of intentional change.